Ask the Advocates: International Overdose Awareness Day

Editor's Note: This article discusses overdose and its impacts, which may be distressing for some readers. If you need support, please reach out to a person you trust or crisis resource. You can also get help here.

Every year on August 31st, we mark International Overdose Awareness Day to remember those we’ve lost to overdose, honor the resilience of survivors, and commit to saving lives.

To commemorate the day, we spoke with four of our health leaders—Dr. Elizabeth Zona, Nate Smiddy, Natalee King, and Courtney Moniz—who have all been impacted by the overdose crisis. Through their stories, they share powerful messages of hope and insight, highlighting the importance of community, education, and compassion in the fight to end overdose deaths.

Their answers remind us that while the overdose crisis can feel overwhelming, we can all play a part in creating a world where recovery is possible and every life is valued.

Advocate perspectives

How has overdose, directly or indirectly, impacted your life or work, and what message of hope do you wish to share with others on International Overdose Awareness Day?

Dr. Zona: I’ve been an anesthesiologist for 15 years. For the first six, I was fully immersed in a world of procedures, precision, and perioperative medicine—and I loved it. Life felt full, and I had no reason to think it wouldn’t stay that way.

Then everything changed. My childhood friend, Teah, died of an opioid overdose. I was devastated—not only by her relapse, but by the heartbreaking detail that people were with her and didn’t call for help. They prioritized their reputations over her life. That truth has never left me.

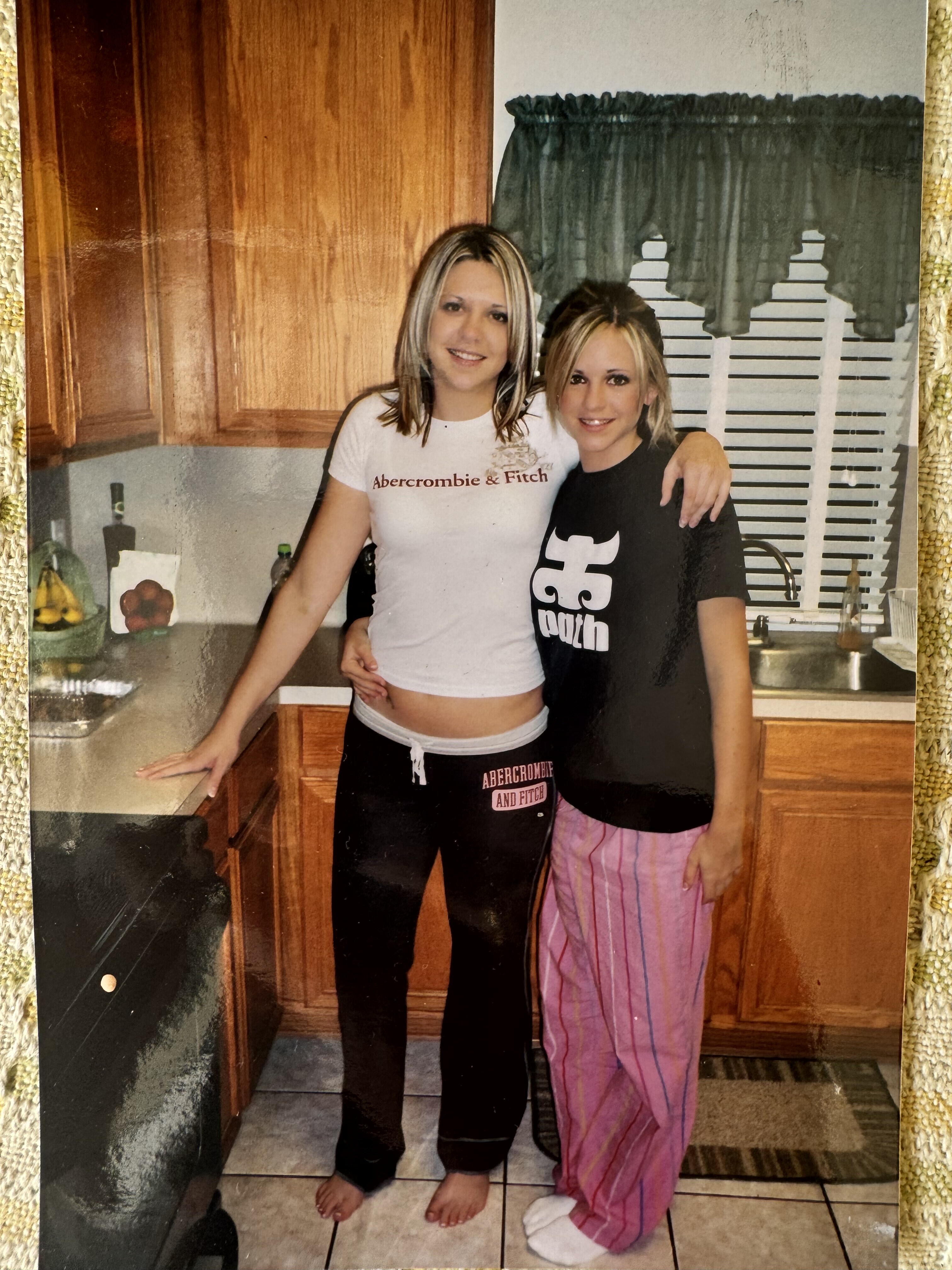

Teah and I grew up side by side. We were so similar as teens—outgoing, full of life. She always made me feel understood and never judged. It was crushing to realize how her early experimentation with prescription opioids altered her entire path. Her story could have easily been mine.

After she died, I felt desperate to go back in time to warn us both how serious this could become. That feeling changed the course of my career. While continuing in anesthesia, I also entered the field of addiction medicine, with a deepening focus on prevention. I now teach youth, families, and professionals about substance risks and the early patterns that can lead to addiction.

I’m especially grateful to Teah’s twin sister, Tahnee, who helps me honor her memory by allowing her story to reach others. Together, we’ve seen how honesty opens hearts and saves lives.

Today, I teach overdose awareness and response because, while I can’t go back and save Teah, I can use what I’ve learned to help save someone else’s friend, sister, or child.

Our pain can have purpose. Our stories matter. And even in loss, we can be the reason someone else gets to live.

Dr. Zona at the Pittsburgh recovery walk wearing her “End Overdose” t-shirt with Teah‘s name on it.

Nate: My desire to get involved and work in harm reduction and advocacy stems from when my friend overdosed in a halfway house. I was the one to find him, and there was no naloxone in the house. I didn’t know about the good Samaritan law back then.

He survived, but in that moment, I knew that other people have experienced this. I knew people were dying because of lack of resources and policy. Some people don’t make the choice I did, and I understand why.

I understood in that moment that the outcome isn't always like my experience. I didn’t want anyone to ever have to be put in my shoes if I could help it. People bury their loved ones over lack of access to a cheap lifesaving medication and a simple common-sense policy.

Because of that experience and realization, I’ve strived to make access to naloxone and other resources as easy as possible. That’s why I started my mailing program, and it’s been incredibly successful. It’s at no cost, and I honor requests regardless of size, if I have capacity.

Thinking ahead is a constant part of my work with overdoses. I'm always questioning and wondering how I can help more and what I can do better. I also consistently ask the people I serve what they need. This has taught me to be as proactive as possible, because most of the time, we are reactive.

I’d say overdoses have traumatized me as well. In the moment I’m fine, but afterwards, I often find myself disassociating and stuck in a loop of past experiences. This work has forced me to make sure I take care of myself so that I can continue to show up.

My message of hope is that while I know we are in tough times, we have survived tough times before. We must lean in on each other and have a support system. We take care of us, and we must never forget that.

Nate distributing naloxone and fentanyl test strips.

Featured Forum

View all responsesWhat is one crucial piece of information or a practical step related to overdose prevention that you believe everyone should know, regardless of their direct experience with opioid use disorder?

Natalee: One crucial piece of information everyone should know is this: You don’t have to be “an addict” for opioids to kill you.

Overdose doesn’t always look like a needle in an alley or someone hitting rock bottom. Sometimes it looks like a teenager taking a pill at a party, not realizing it’s laced with fentanyl. It looks like someone with a back injury taking a painkiller a friend gave them—just one. And that one is the last.

That’s why fentanyl test strips and naloxone (Narcan) matter. That’s why education matters. Because prevention isn’t just for people in active addiction—it’s for everyone. It’s about making sure our kids, our families, and even strangers we’ll never meet have a fighting chance.

I lost my sister, Niki, to a drug overdose. It shattered everything. If we had known then what I know now—about harm reduction, mental health, how quickly things can spiral—we might still have her.

So I speak up. I go into schools and talk to parents. I carry Narcan in my bag and tell people they should, too. Because this isn’t just a “drug problem.” It’s a public health crisis. And silence isn’t going to save anyone.

The practical step is simple: get trained on how to use Narcan and keep it with you. It’s easy, it’s legal, and it saves lives. You’ll never regret being the person who was ready to help.

Even if you’ve never struggled with addiction yourself, I promise—it’s closer to you than you think. And the life you save could be someone you love.

Natalee and her sister, Niki.

Featured Forum

View all responsesWhat does community support mean to you in the context of preventing overdose and supporting recovery, and how can we strengthen these bonds?

Nate: For me, community support is a network of people—whether in recovery or not—that support me on this journey of recovery regardless of where I am in my journey.

That could be a case manager, a friend, or a co-worker. It could be anyone that’s a positive influence in my life that can help me by giving suggestions or guiding me when I’m lost and facing something I’ve never faced before, especially when I’m most vulnerable. Whether I'm still using, in early recovery, or going through some challenging trials and tribulations, I need someone who listens to understand, not just to respond.

I also think it’s important for those of us who have been in recovery for awhile to not forget where we came from. Often, people who have been in recovery for some time forget what it was like, and a lot of what they say and do is harmful to those still struggling. We need consistent compassion and empathy.

People say the opposite of addiction is connection. If so, then one must ask themselves, "How do I cultivate and maintain a connection with someone who is in recovery and what does that look like for me?"

I think to answer this question, we must address our own internalized stigma. I’ve had to do it as well. I realized my thoughts and beliefs at one point were harmful and weren’t conducive to the people I served. It was hard to reprogram my mind, but in time, I was able to support people by challenging my thoughts and ideology around substance use.

Lastly, I think we achieve best practices by challenging our thoughts and ideas and continuing to educate ourselves about best practices and even asking simple questions such as, "How can I best support you?”

What is one concrete action, big or small, that you encourage individuals or communities to take this International Overdose Awareness Day to make a difference in the fight against overdose?

Courtney: For International Overdose Awareness Day I want to call on everybody to keep something in mind: we are all human beings.

Often people suffering with opioid use disorder are dismissed as just another statistic. Communities across this nation are becoming desensitized to this ongoing epidemic. They are no longer shocked when they see people suffering with opioid use disorder walking the streets. They have adjusted. Because of this, I feel that people struggling are less humanized than ever before.

Kindness is free and has the power to transform lives. Becoming aware of local resources in your area is also free. When we consciously humanize these people and learn their stories, they transform from a statistic to an individual.

These are peoples’ children and parents. They are our veterans, our friends, and our neighbors. Many of them are victims, and each and every person struggling with opioid use disorder deserves healing. It's easy to only judge people on the surface, but remembering that we all have a story is extremely important.

Kindness ripples through the lives of people coming out of opioid use disorder. For me, it felt fundamental. In my experience with my own opioid addiction, I was counted out and told by many that my fate was ONLY prison or death.

This week I graduated college, earning my first degree and beginning my bachelor this month. This upcoming January I will have 8 years of freedom from my opioid use disorder. I got here through the support of others willing to educate themselves.

I am grateful beyond measure that my support system offered me a foundation to rebuild myself through being kind and viewing me as a human being in distress. I wish the same for others still suffering, because the value in that kindness is priceless to the recovery process.

Courtney during active use and now, 8 years into her recovery.

Featured Forum

View all responsesWhat is your vision for a future where overdose deaths are significantly reduced or eliminated, and what role do you see individuals, communities, and healthcare systems playing in achieving this?

Dr. Zona: After years of rising losses, we’re finally seeing signs of real progress—and that gives me hope.

In 2023, overdose deaths began to decline for the first time in years, dropping from 112,600 to around 105,000.1 In 2024, the shift was even more dramatic: a 27% national decrease, with deaths falling to roughly 80,400—the lowest since before the pandemic.2

Young people led the way. Compared to the peak, an estimated 15,000 fewer lives were lost under age 35. College-aged adults saw the steepest decline, and teen deaths fell to their lowest level since 2013.3

These aren’t just statistics—they represent lives, futures, and families still intact. This is real hope, earned through real work.

As an Advisory Council Member for National Fentanyl Awareness Day—an initiative led by the nonprofit Song for Charlie—I’ve worked closely with their team to amplify youth-focused education and prevention.

Founded by Ed and Mary Ternan after losing their son Charlie to a single counterfeit pill, Song for Charlie has become a national leader in this fight. Ed recently shared his cautious optimism: young people are finally getting the message, and it’s saving lives.

I believe that, because I see it firsthand. I’ve been out in schools and communities teaching prevention, and Song for Charlie’s resources have been vital to that work. Families and educators are replacing silence and fear-mongering with science and facts. Education is saving lives.

This shift isn’t accidental—it’s the result of intentional, persistent work. I’m proud to be part of it.

Prevention works. Recovery is possible. Lives are being saved.

In your opinion, what is the most significant misconception about opioid use disorder or overdose, and how can we collectively challenge it?

Courtney: In the beginnings of opiate use disorder, when it still feels recreational, being “high” without withdrawal is entirely different than what the rest of that journey becomes.

The part of the nightmare without the withdrawal factor doesn’t last very long. Eventually, it stops being about getting, “high” and becomes about getting well and being functional. It turns on you, quickly.

I remember realizing that I needed heroin to appear “straight” at my daughter's elementary school function. I wasn’t “high”—it was not this fun time that people assume people suffering with opioid use disorder are having. I was functional.

A significant misconception about opioid use disorder is that loved ones often assume that continued opiate use is a simple choice. They would often ask me, “Why can’t you just stop?” I was asked that over many years.

What my loved ones didn’t realize was that I wanted to stop, too. The physical and psychological impacts of opiate withdrawal develop into such a profound control over our decision making, over our health, our families, even our own children.

It’s not just a simple choice to keep using. It’s a spiritual struggle between the part of you that desperately wants to stop and the part of you that fears the agonizing and extraordinarily soul shattering withdrawal. It’s a dilemma, and it’s a family disease.

Thankfully, it’s something that can be resolved, something that can be survived. We really do recover.

Natalee: One of the most damaging misconceptions about opioid use disorder is the belief that it only happens to “those kinds of people”—that it’s a result of poor choices, bad parenting, or weak character.

But addiction doesn’t check credentials. It doesn’t care where you live, what you believe, or how much potential you had. It can happen to the star athlete, the straight-A student, the devoted mom, the war hero. It happened to my sister, Niki—someone with a huge heart, a magnetic personality, and so much love to give. Her addiction didn’t make her a bad person. It made her a person in pain.

The truth is, opioid use disorder is a disease—often rooted in trauma, mental health struggles, or untreated emotional pain. But the shame attached to it keeps people from getting help. Families stay quiet. People suffer in secret. And the silence becomes deadly.

To challenge this, we have to start telling the truth—out loud and often. That means sharing real stories. Humanizing the faces behind the statistics. Correcting misinformation when we hear it, even when it’s uncomfortable. It means educating others that relapse doesn’t equal failure, and that recovery is possible—but it looks different for everyone.

We change the narrative by refusing to let shame lead the conversation anymore.

Every time we speak up, every time we show compassion instead of judgment, we’re breaking down a wall. And that matters because someone is always listening. And the story you share might be the one that saves them.

This isn’t a “them” issue. It’s an all of us issue. And the sooner we see that, the more lives we’ll save.

Featured Forum

View all responsesTo learn more about International Overdose Awareness Day, click here.

Join the conversation